How Purposeful Practice in Math Drives Student Achievement

2-min. read

2-min. read

By: Liana Roth

The short and simple answer is: the English language is weird.

Think about it. I bet you can come up with a whole list of rules no one quite understands and another long list of words that break the rules on the first list! Check this out:

When you stop to consider how many rules our language has and how many times those rules are broken, it’s no wonder learning to read can be so tough—even for native English speakers.

The Science of Reading is really just decades of evidence-based research from a variety of fields that focuses on how our human brains learn to read. And make no mistake about it—learning to read requires our brains to work hard!

When toddlers learn to talk, they pick up sounds and words organically through exposure. We all learned to speak because we heard other people talking around us and, even more importantly, talking to us.

Reading research challenges the misconception that humans learn to read the same way they learn to talk. Reading may be automatic for you and me now, but learning to read once required our brains to work very hard.

Although it can certainly be helpful, surrounding children with books, reading aloud to them, and reading with them is simply not enough for most children to learn how to read. Reading research indicates that except for a minority of gifted students, systematic and explicit instruction is necessary to learn how to read.

When you’re teaching your students to read, the curriculum should start with the basics and build from there. Emerging readers must master their sounds before letters, letters and sounds before words, words before sentences, and sentences before passages.

When students learn to read methodically, the concepts build on one another, so they can master each skill and gain confidence before moving on.

Reading science has shown that students of all reading levels—whether they are below, at, or above grade-level proficiency—develop the ability to read faster when provided with systematic and explicit instruction.

To read a single word, our brains have to:

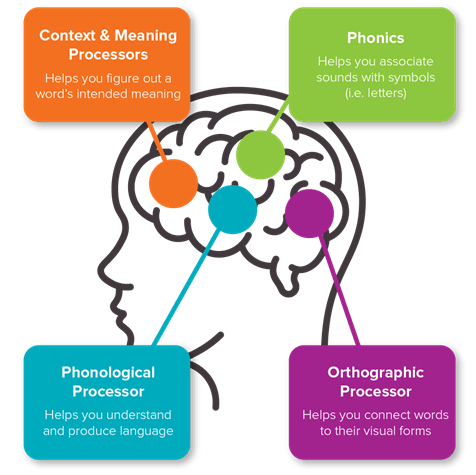

That process can only happen when four different regions of the brain work together. Our Phonological Processor helps us make sense of the sounds we hear so we can understand and produce language. This works in tandem with the Orthographic Processor to connect words to what they look like visually. With this information, we use Phonics to connect sounds with symbols. Finally, the Context and Meaning Processors help us figure out a word’s intended meaning.

When our brains make these connections to read a word, we store the word permanently in a process called orthographic mapping. The ultimate goal is to map thousands of words over time so that reading words—and understanding them—happens automatically. But for beginning readers in our classrooms, we have to teach the skills that lead to orthographic mapping explicitly and systematically.

Understanding the Science of Reading and its implications within the classroom is a sizable undertaking that you are not going through alone. In fact, most educators across the country are now learning new information that was not covered during college or in their training.

To learn more, check out our free webinar series—Science of Reading: Putting Research into Action.

2-min. read

2-min. read

3-min. read